“Why Should I Bother?” – The Underachieving Student

We all have moments where we ask ourselves, “Why should I bother?” If we don’t see value in something, we’re unlikely to put effort into it.

Back in high school, I already knew I wouldn’t be pursuing anything related to math. So I skipped classes, didn’t study for tests, and turned in blank assignments. But I wasn’t too frustrated because I had subjects that kept me engaged—history, literature, and dance.

However, some students don’t feel this way about any subject. They don’t see the value of school at all, so they disengage entirely.

Meet Tom

Tom is a bright 10-year-old child who doesn’t like school. He has an exceptionally large repertoire of facts and an astonishing understanding of concepts when he is interested. He can concentrate for hours on something when he likes it.

But when it comes to schoolwork, Tom gives up when things get challenging, loses interest after a few minutes in most subjects, hands in incomplete schoolwork, and chooses the easy way out whenever he can.

Tom constantly argues with the teachers and thinks school is irrelevant to real life. You will often hear him saying, “why do I need to learn this?”, “it’s boring”, and “it’s good enough”.

Observing Tom’s (high) potential compared to his (low) achievements, his parents have realized he is underachieving.

In Tom’s case, as in many other underachievers, we see the “why should I bother?” case.

There are two basic reasons that Tom would be willing to engage in a task:

He enjoys the activity, or he values the outcome of the activity.

Tom will be willing to “perform” when he studies a relevant subject (in his opinion). Many children are not motivated to achieve in school because they do not value school outcomes, nor do they enjoy completing schoolwork; therefore, they lose interest.

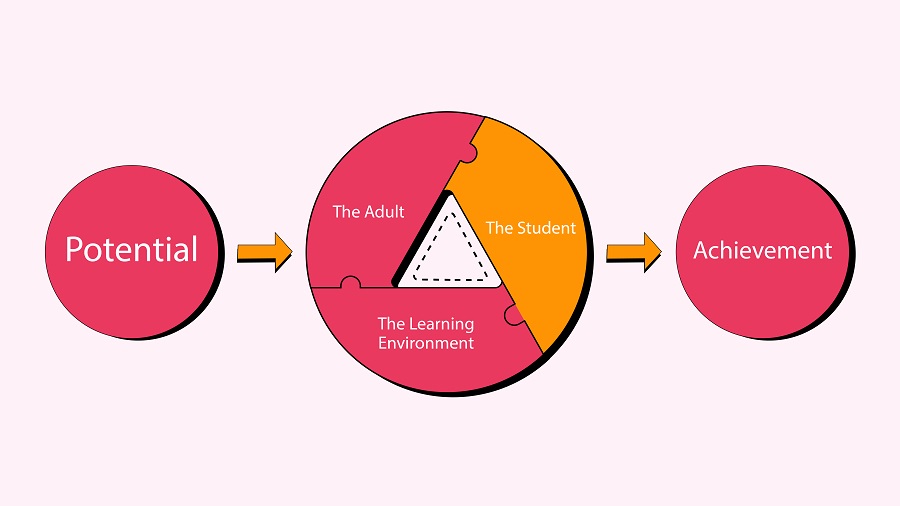

The Student’s Role in Underachievement

Underachievement is influenced by three key factors: the student, the adults around them, and the learning environment. Today, we’re focusing on the student’s role.

1. Growth vs. Fixed Mindset

Carol Dweck’s research highlights the difference between students who embrace a growth mindset—believing that effort leads to improvement—and those with a fixed mindset, who see abilities as innate and unchangeable.

Growth mindset students say:

- “Let me try another way.”

- “Mistakes help me learn.”

- “This may take some effort.”

Fixed mindset students say:

- “I give up.”

- “I’m not good at this.”

- “This is too hard.”

What can we do?

Encourage effort over results. Instead of saying, “Good job!” when a student completes a task, try, “I saw how much effort you put into this—I’m proud of you!” Gradually shift the focus from innate ability to perseverance.

2. Unrealistic Expectations

Setting expectations too high or too low can discourage students. If the bar is too high, failure feels inevitable. If it’s too low, there’s no challenge to rise to.

Example:

Tom dislikes art. He’s been told for years that his work lacks effort, so he stopped trying. He convinced himself that he’s “bad at art,” so handing in rushed, low-quality work became his norm.

What can we do?

Help students set realistic, achievable goals and understand that growth takes time. Adjusting expectations gradually, rather than drastically, prevents overwhelm and resistance.

3. Handling Competition

Competition can boost motivation, confidence, and resilience. But if a student doesn’t know how to handle losing—or avoids competition altogether—it can hinder achievement.

Example:

Tom loves competition—when he wins. But when he loses, he either quits in frustration or blames external factors. His reaction to competition impacts his motivation in school.

What can we do?

Model healthy competitive behavior. How do we react to our own failures? Do we make excuses, avoid competition, or see setbacks as learning opportunities? Our students absorb more from what we do than what we say. Watching documentaries or reading stories about successful people who overcame failure can also be powerful.

“The key features that distinguish achievers from underachievers are the goals they set for themselves and effort they put forth to achieve these goals.”

McCoach and Siegle

Reframing “Why Should I Bother?”

Tom’s experience was different from mine—I had subjects that kept me engaged, but for students like him, school as a whole can feel irrelevant. Instead of dismissing their frustration, we can ask:

“What would it take for you to do well in school?”

This question gives students a sense of control over their learning, and their insights may surprise us.

Let’s make sure all students feel engaged and fulfilled in their education. Looking for ways to reverse underachievement? Let’s talk.

If you like my posts, sign up for my newsletter to get more tips in your mailbox (I don’t send spam, only good things).